From Innocence to Decay

As a child in the 1960s, I remember British beaches in a way that now feels almost unreal. Bridlington, Walton-on-the-Naze, Leigh-on-Sea… long stretches of sand and shingle where the most exotic intrusion was the occasional washed-up jellyfish or a stray wrapper blowing in from someone’s picnic. The shoreline was a place of innocence; you ran towards the sea, never pausing to wonder what was floating in it. Even in towns with busy estuaries, the worst you might step on was a shard of old bottle glass worn smooth by years of erosion, or a length of frayed rope.

A Tide of Poison

Half a century later, you would struggle to find a coastline anywhere that still resembles that memory. Storms, monsoon swells and shifting currents have become conveyor belts for the artefacts of our excess. Every tide reveals what we have been discarding for decades: plastic bottles, drink cartons, fishing line, food packaging, polystyrene, abandoned nets, and microplastics embedded in the sand like malignant grains. Billions of fragments – light enough to drift for years, toxic enough to outlive us all – spreading across the planet like a tide of poison that never recedes.

A Dystopian Message In A Bottle

What would once have shocked now barely registers. Children move through the debris as if it belongs. Tourists step over the washed-up rubbish as if it were driftwood. Local authorities rake the top layer of sand to preserve the illusion of order. We have adapted to filth without realising how completely it has colonised the edges of our lives. Even the seabirds pick through the same debris now, not mistaking it for food but simply finding it everywhere they turn. What should be sand and sea has been replaced by this new, synthetic terrain.

“Water and air, the two essential fluids on which all life depends, have become global garbage cans” – Jacques Cousteau

Scientists estimate that up to fourteen million tonnes of plastic enter the oceans each year. Microplastics now fall in Arctic snow, sit in the sediment of the Mariana Trench, and circulate inside human bloodstreams. They have colonised the biosphere more thoroughly than we ever colonised continents. It is not a metaphor. It is the world as it is.

Back then the tide brought shells and seaweed. Now it returns our rubbish like a message in a bottle, though one we still refuse to read.

Slow Decline

Because this is what collapse looks like. Not sirens, not riots, not dramatic tipping-points. Just a slow, grinding acceptance of ugliness. A civilisation adjusting to decay in real time, as long as the Wi-Fi still works.

Nature attempts to compost what it can: palm debris, rotting vegetation, the brittle remains of coconuts. But mixed through it all is the stuff it cannot break down. A permanent record of our carelessness, washed ashore with every tide.

The dystopia is not in the future. It is already here. It arrived quietly, wave by wave, bottle by bottle, shrug by shrug.

“But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself” – Rachel Carson

Civilisations rarely fall in a single dramatic moment. More often they dissolve under the combined weight of their own ignorance, pride and, in the 21st century, detritus. We have microplastics in our seas, soils, skies and blood. We build floating garbage islands large enough to be seen from satellites. Our children weave between discarded drink cartons, broken flip-flops and syringes.

“The ocean is the heart of the planet. If the oceans die, so do we” – David Attenborough

Sisyphus, Beach Version

And then there is the scene on the beach in the photos: one lone man, bent over like an aging Sisyphus, stuffing rubbish into an old dog-food sack. Earnest, futile, resigned – an act of defiance against a world that long ago stopped listening. Even caring. A tiny gesture in a collapsing system. Not enough to change anything, but just enough to show that someone, somewhere, is still paying attention.

A small protest against indifference, against entropy, against the slow drowning of a species in its own debris.

UPDATE – latest news, 24/11/2025

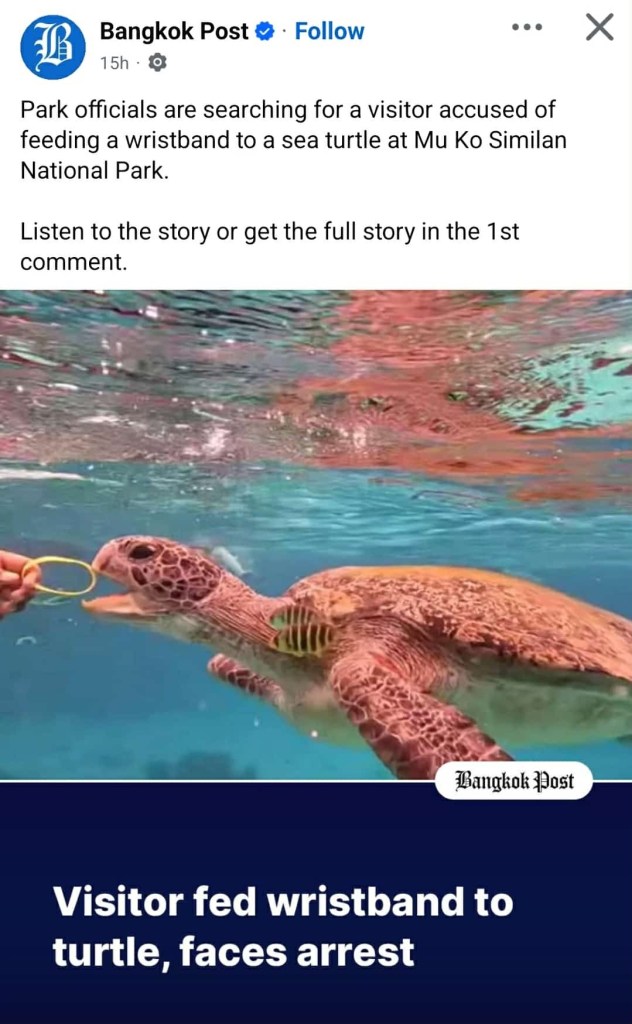

Another day, another tourist offering the local wildlife a taste of our civilisation. Plastic, brightly coloured, and guaranteed to outlive the turtle by several centuries.