Early 2000s: Over a couple of decades living and working around France, I came across a fair few Brits who – to all appearances back home – no doubt seemed rational and pragmatic people, comfortably settled in their professional and domestic lives. Yet on holiday across the Channel, quiet plans took shape. They yearned for something more. Not just a break. A better lifestyle. The dream was semi-retirement in sun-soaked simplicity, à la française, whether or not they spoke more than a smattering of French or had grasped the true costs of running gîtes in rural isolation.

Provence was particularly magnetic for these wide-eyed hopefuls. Peter Mayle’s A Year in Provence (1989) had created a whole new mythology: rustic bliss, village fêtes, lavender fields, cicadas. That book did for Provence what Eat Pray Love did for yoga retreats. You could almost hear the sound of estate agents rubbing their hands in glee. It’s no coincidence that Sotheby’s planted a branch in Gordes around that time – the hills of Provence had become a brand.

I would occasionally find myself – reluctantly – chatting to would-be expats over a drink. Certain triggers – “we’re thinking of opening a B&B”, “we’ve enrolled in an intensive French course” – set off alarms. I offered a few well-meaning caveats. A few listened. Others didn’t.

They sold up their three-bed semis back home, racing ahead with an impulse ‘bargain’ purchase of a vast if crumbling edifice, frequently in the middle of nowhere. Their Gallic Shangri-La. Yet the grass, it turned out, could be less than a luxuriant shade of green. A brittle, sun-frazzled beige in need of constant watering and care.

One case sticks vividly in my mind. It was 2003. Not far from our place, down in the Ouvèze valley, stood a large, dilapidated farmhouse that had been on the market for years, at a greatly inflated price. It was, in estate agent parlance, “full of potential”. Translation: structurally unsound, inconveniently located, and uninhabitable without a massive injection of cash. Yet one bright March morning, for a retired British couple – she a school inspector, he a headteacher – it was love at first sight. They signed on the dotted line.

They hadn’t done any homework. Hadn’t spoken to anyone local – like us, just a few hundred metres up the hill – who could have told them exactly why the place had been on the market for so long. Natural British reserve, perhaps. Or more likely that habitual self-assurance, the quiet assumption that they knew better than the natives.

The valley looks idyllic in spring. Crisp air, birdsong, the quiet gurgle of the river. But what they hadn’t noticed was the road. A surprisingly busy departmental route, just fifty metres from the house. Come summer, it would become a thundering corridor of tourist traffic. Cars and caravans roared through, bouncing noise off the steep valley sides like a natural amphitheatre. The windows shook.

It didn’t take long. Within days, they were already thinking of selling. I dropped by and offered support and local contacts, but was swiftly dismissed – “Our son is a lawyer in Geneva”. I bit my lip; their son could have been senior partner at Kirkland & Ellis for all the difference that would make in our Provençal backwater.

But they didn’t give up. They overcame their misgivings, and with true British grit and determination, brought in a stream of architects, engineers, and landscapers. Massive earthworks were undertaken to build a noise-deflecting wall. Huge expense was incurred. Views sacrificed. And still, during certain hours, you had to raise your voice to be heard indoors.

Then came the first of their legal battles. They tried to block an ancient droit de passage – a right of way that passed near the house. I warned them not to waste their time. They of course ignored the advice and cordoned off the passage with chains. Local farmers bulldozed the barriers, promptly and without ceremony. In this part of the world, you don’t overturn centuries-old rights of access because your brunch is being disturbed.

Next – the coup de grâce.

On a visit home from an extended stay in Savoie, the house was gone. Completely. Apparently, they’d given up on the renovation and, on a whim – following some dodgy advice – had bulldozed it to rubble. They’d been told that knocking it down and starting completely from scratch would be simpler.

A bigger mistake they could not have made.

What they hadn’t realised was that, under French planning law, once a building on agricultural land is demolished, its residential rights vanish with it – a far more rigid system than Britain’s looser patchwork of green-belt and rural zoning rules. Meaning it’s not a house anymore. It’s a field. You can’t rebuild on a field. Not a house. Not a shed. Nothing.

They tried everything to claw something back – including one particularly ambitious application to turn the land into a 25-room hotel with a sulphurous spa, using a spring that happened to rise on my neighbouring property. The local mayor was not amused. Or fooled. They pled their case to the departmental préfet, and finally went to judicial appeal – all in vain.

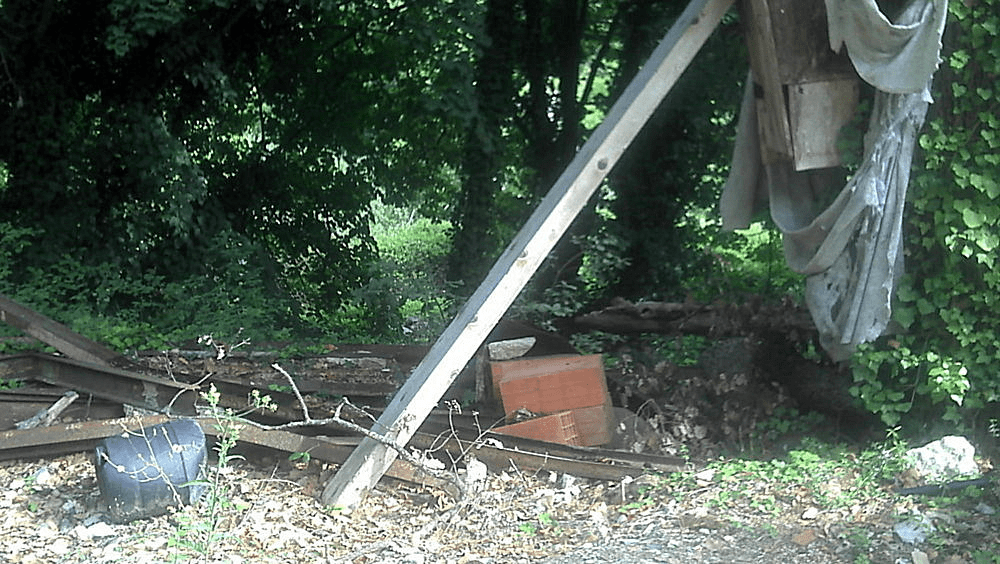

The DDE (Direction Départementale de l’Équipement) ruled promptly and decisively. The dream was dead. All that remained was a large hole in the ground, a few sad trenches with rusting rebar, and two deeply embarrassed and extremely angry retirees.

By 2011, the whole site – piles of stone, weed-covered foundation trenches, two hectares of farmland – was quietly put up for sale. Asking price €10,000 – the full stop to an adventure that had already cost them many hundreds of thousands, and rather more in blood, sweat and tears.

Two neighbours, armed with the required farmer status giving them priority over other offers, had their eyes on converting a couple of ruined outbuildings into holiday gîtes. One asked me to provide a letter supporting her bid. I was aware that the original tip-off enabling the authorities to miraculously turn up in the few hours between the last wall coming down and the new one going up came from an all-too-local source. But in the final analysis, it was hubris that brought about the Brits’ downfall – not unscrupulous French neighbours.

What happened to our overconfident, naïve and unprepared dreamers? They had no choice but to abandon one of the most expensive fields in Provence. And leave behind a story the locals still recount, with a mixture of pity, schadenfreude, and a Gallic shrug.

Greenness, after all, isn’t just about the hue of the grass on the other side of the fence.

The field – 2011

Postscript 2025: The New Reality

With Brexit long behind us and nationalism again on the rise across Europe and the United States, attitudes have hardened. Borders too. The easy mobility of the 1990s and early 2000s now feels like another age.

After the Maastricht Treaty created EU citizenship in 1993, Brits enjoyed the freedom to live and work anywhere in the EU – a privilege that quietly rewrote thousands of midlife plans and retirement dreams. A Brit could pack up, drive south, and settle anywhere in France with little more than a ferry ticket, an address, and the conviction that they’d “made the leap”. Bureaucracy existed, but it was mostly local and surmountable.

Today, it’s different. Since Brexit, British citizens are classed as third-country nationals – legally no different from Colombians or Belarusians when it comes to settling in France. Anyone wishing to move permanently must first obtain a long-stay visa before entering France, then apply for a residence permit. For those retiring or living on private means, the rules are tighter: proof of accommodation, comprehensive health insurance, and sufficient income – typically assessed around the net minimum wage (≈ €1,400 per person per month) or equivalent savings.

The easy cross-Channel drift for Brits post-1993 has vanished. Dreaming of Provence remains free; living there now comes with an administrative price tag. For many would-be émigrés, the grass may still look greener, but these days you need to prove you can afford to water it.